Mass, Not Subject: Reading AI Images Through Gradient Fields

Most people look at AI-generated images and see:

a butterfly, businessman, waterfall, vase of flowers and cathedral

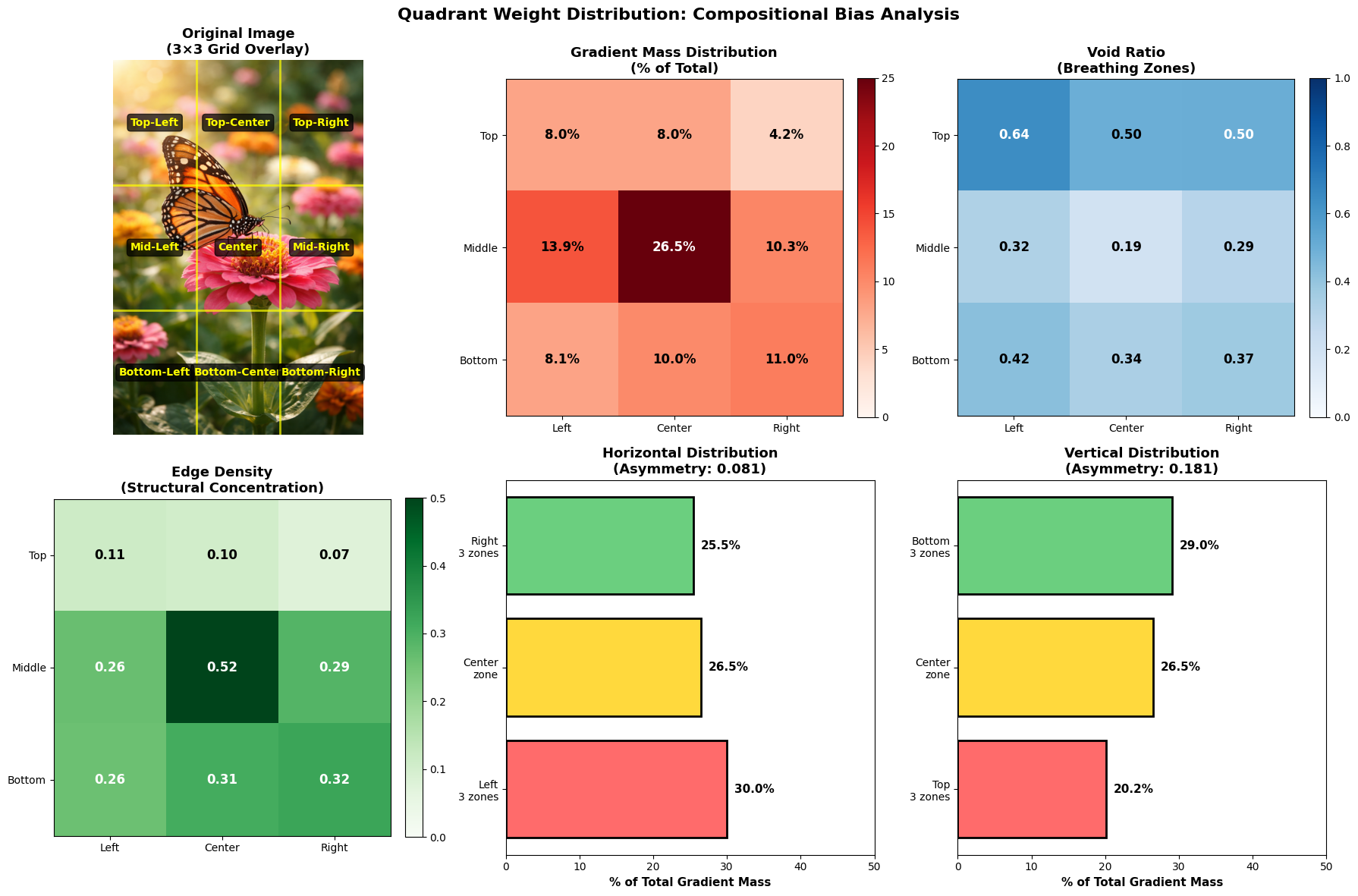

Artists and gradient analysis see something else: Where visual mass lives, how space breathes, and what holds the frame together.

And across engines, styles, and prompts, “mass” is not the object.

Mass is edges, contrast, tension, structure, the skeleton under the picture.

The kernel measures that structure, so artists, researchers, and engineers can finally talk in the same language.

Why “mass” matters and why everyone means something different

Most viewers interpret images semantically:

“The butterfly is on the left.”

“The man is centered.”

“The waterfall is near the top.”

But that’s not what the image is doing compositionally.

Viewers see subjects.

Artists see geometry.

Researchers see gradients.

Engineers see high-magnitude pixels.

And all three are describing the same phenomenon.

When we remove subject labels and reveal edges, contrast fields, and structural weight, the frame reorganizes and through a common language, we can actually begin to speak together. In a weird way, AI can actually unite the field of view.

What “mass” actually is

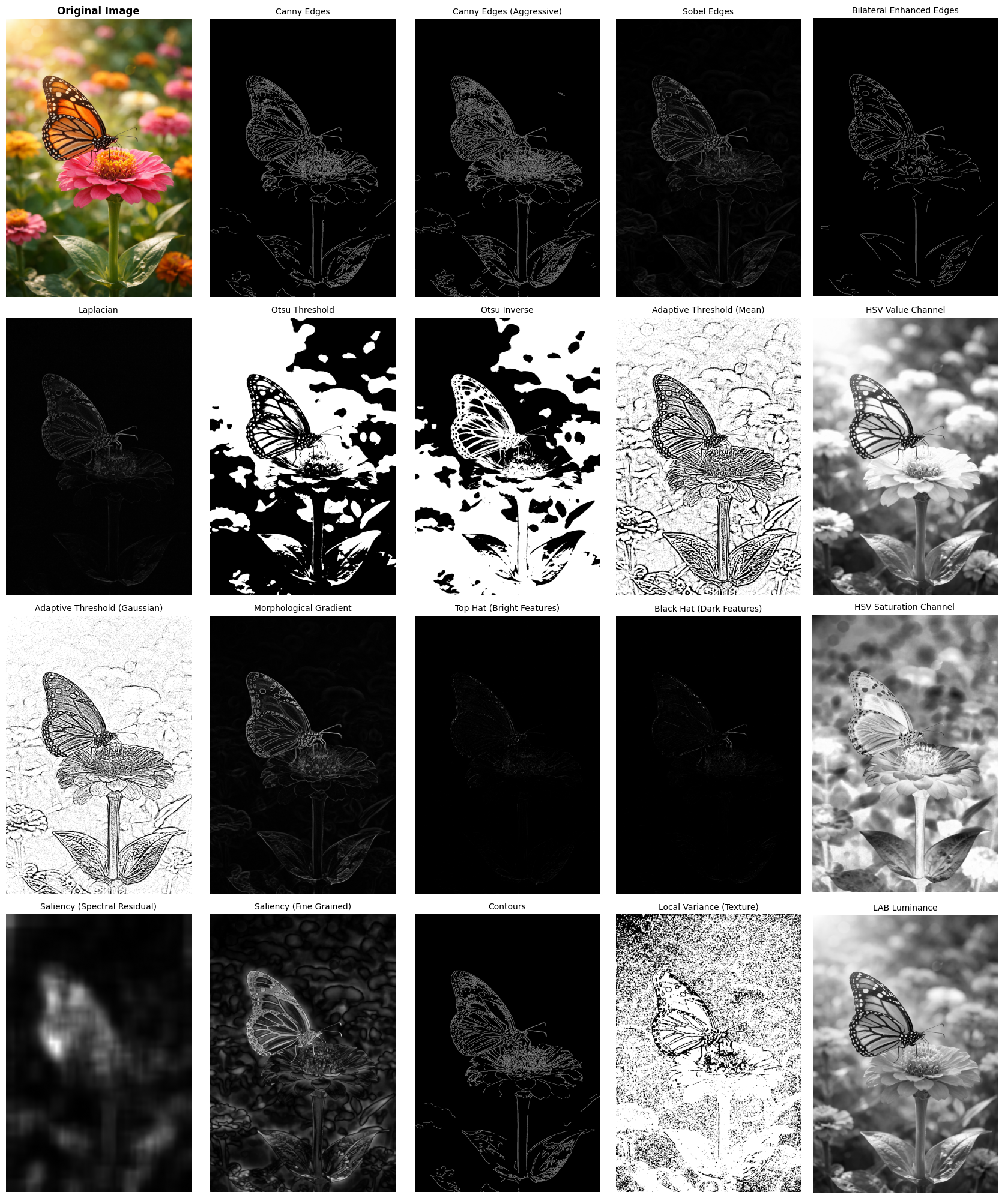

First, it is important to shift the understanding of when analysis says “this image is centered” and the viewer looks at it and sees a figure is off placed - it is not the subject, it is the “mass” that is being referred to. This is a shift from subject to what holds an image together. This will define mass in three different languages, and shows they land on the same truth:

Artists: dark shapes, bright highlights, hard edges, structural tension

Researchers: high-gradient regions in the luminance field

Engineers: pixels above the 75–85th percentile after gradient filtering

All pointing to the same idea:

Mass = regions of rapid visual change — where structure lives.

Suddenly, the butterfly that appears “left” is not so left. When combined with the flower, the shapes and shadows around it, all viewers can start to see that the image isn’t composed “left,” it is suddenly a structural mass that is nearly centered.

The machine flattened the subject and through a variety of filters can expose composition, where many may miss it. It exposes, in a way, what artists see when looking at the image of the butterfly.

Mass = gradient, not object

It is a geometric measurement independent of human evaluation.

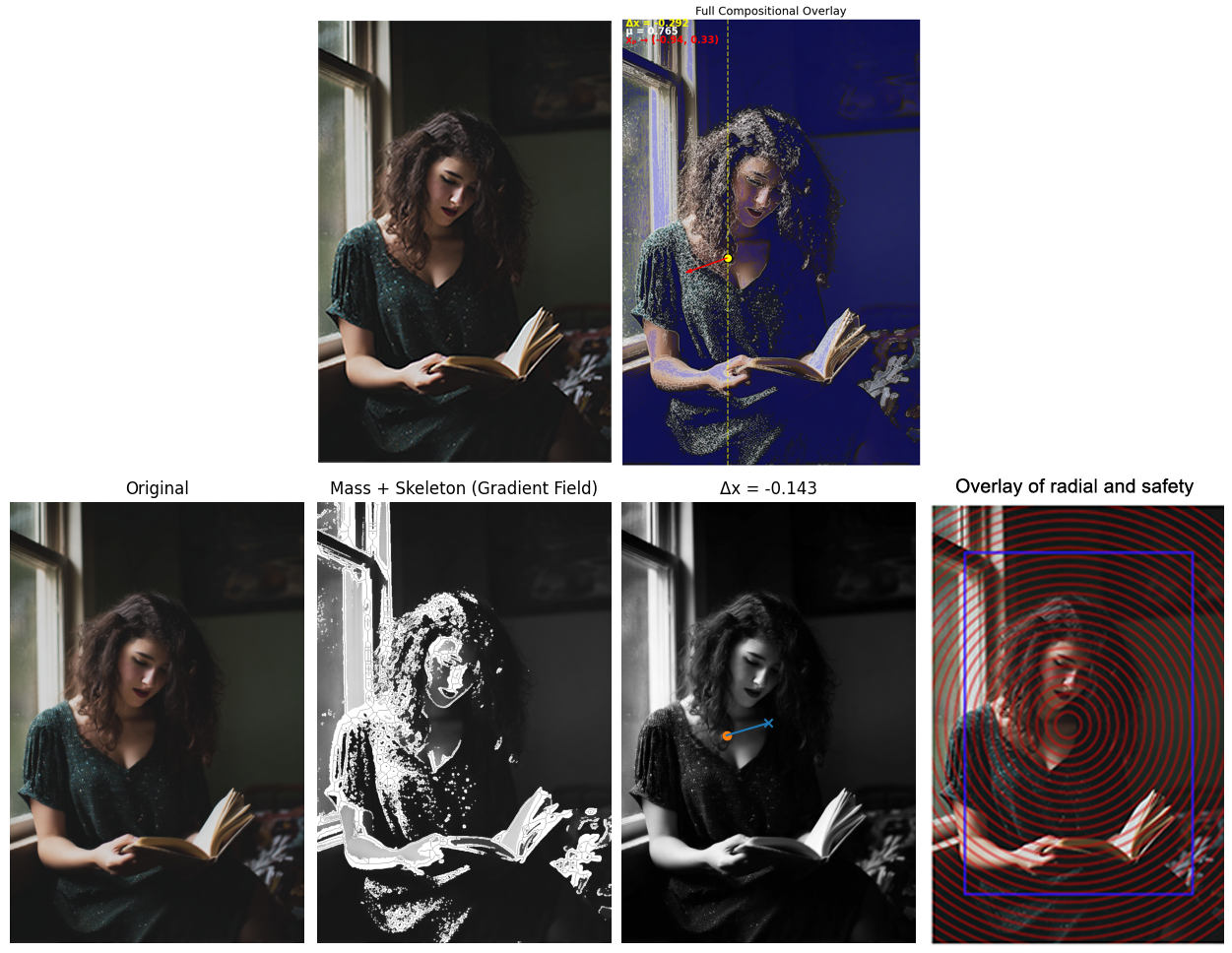

The example that breaks intuition: the woman by the window

Humans say:

“She’s clearly left-weighted.”

Gradient analysis shows something else:

book edges pull center

window frame mass anchors left

hair volume counterbalances right

blinds create vertical tension

voids cushion everything

Result:

Gradient-weighted centroid: Δx ≈ −0.143

Not off-center — structurally stable, inside the central envelope.

Not perfectly centered, but far less left-weighted than semantic perception suggests, the central stability envelope.

The structural mass is more balanced than the subject placement, meaning humans see a strong left, but the weight of the mass is in totality, is not far off center.

The figure is left.

The mass is not.

Compositional reasoning vs. semantic understanding

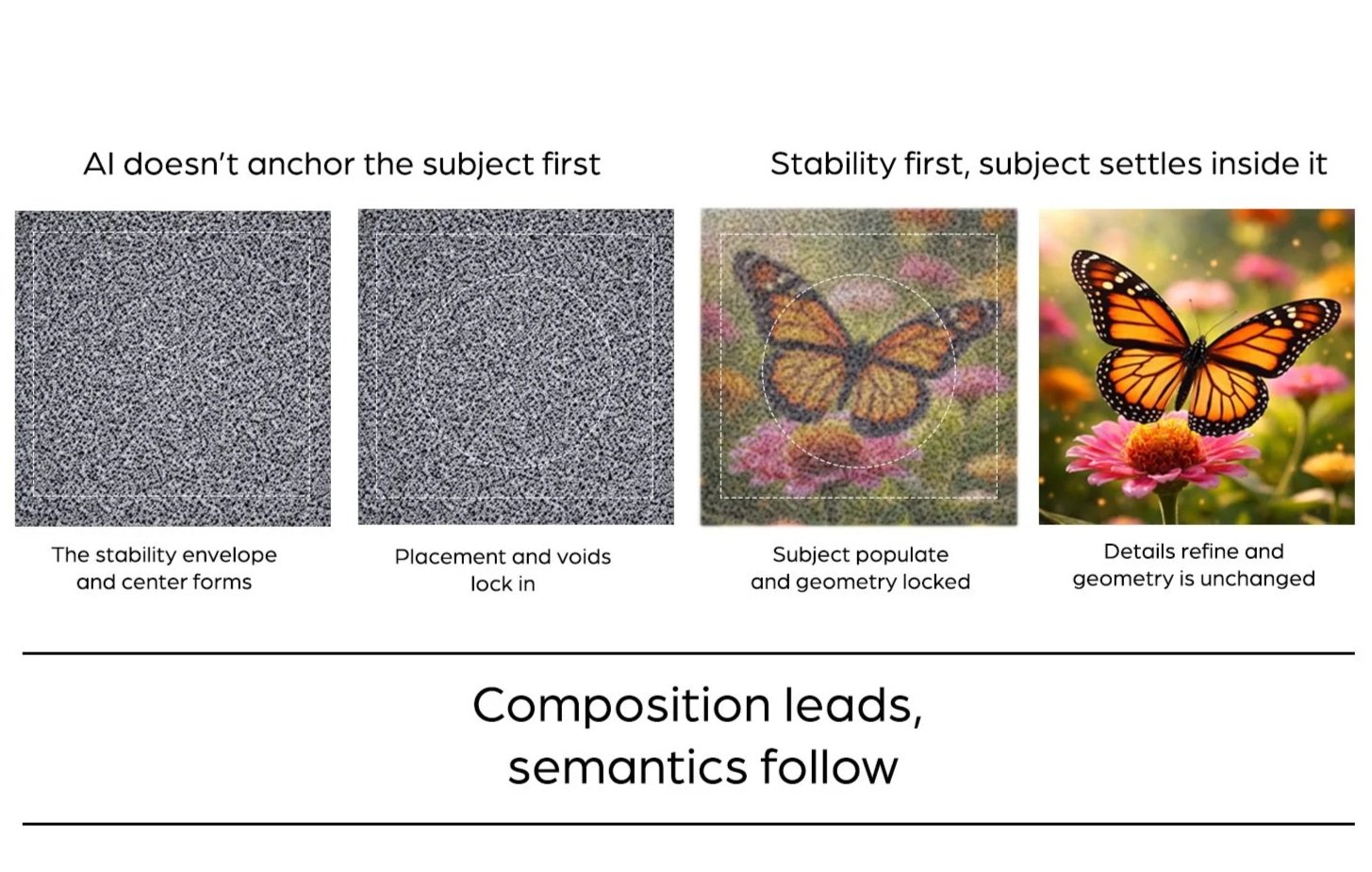

Diffusion doesn’t build subjects first — it builds structure first

The Process Users Don't See: Why Δx ≠ Subject Placement

Users think: Model "draws" the subject, then fills in background

Reality: Model refines entire frame simultaneously through ~50 denoising steps

Steps 1–10:

layout + radial attention field form

Δx and rᵥ LOCK INSteps 10–30:

subjects populate the fieldSteps 30–50:

details refine — but composition is already frozen

The user sees step 50. The compositional constraint was set at step 10.

Not “is this a butterfly?”

But “how does this image hold itself together?”

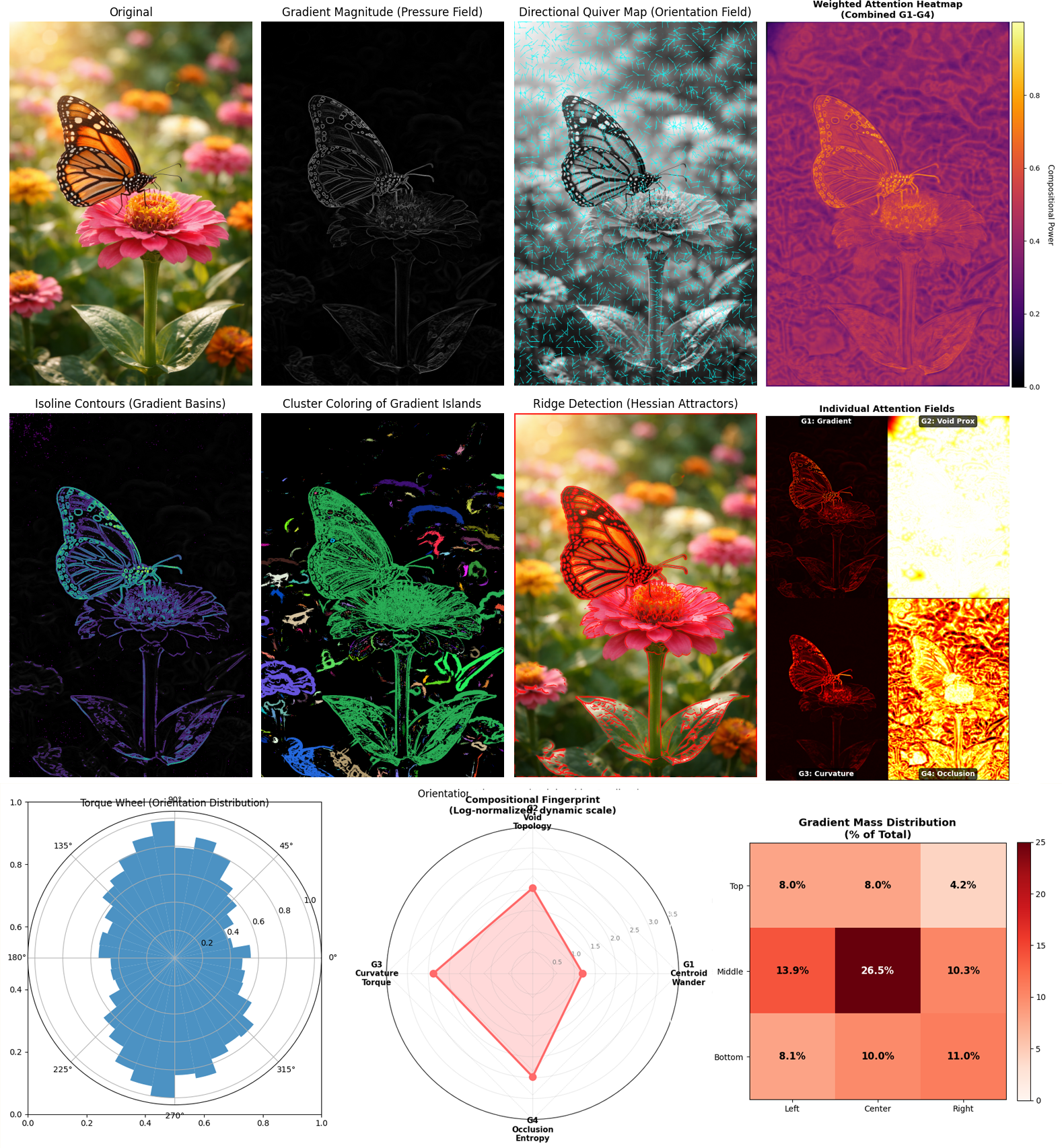

Enter the kernel: the translator between worlds

We bridge this perception gap through seven gradient-field kernel metrics measuring compositional structure independent of semantic content. "Mass" means edges, contrast, visual weight and not subjects. The seven kernel metrics don’t judge aesthetics.

They measure structural truth:

Δx — where mass sits

rᵥ — how much emptiness governs the frame

ρᵣ — how tightly detail clusters

μ — whether it behaves as one unit or many

xₚ — edge pull vs center pull

θ — directional coherence

dₛ — thickness of structure

They are model-agnostic, reproducible, and contrast-independent. These metrics are invariant to subject matter, color, texture, and prompt wording.

They turn “intuition” into numbers.

These kernels measure different things, and that difference is critical. In these futures, different masks are applied to illustrate how AI, researchers and engineers understand an image, what is being formed and organized.

There is no ground truth for "correct" composition

But there is ground truth in understanding composition

How the kernel reconciles artists, researchers, engineers

Artists say:

“Everything is centered and safe.”

Researchers say:

“The centroid and void distribution prove it.”

Engineers say:

“The gradient field shows early-stage stabilization.”

The kernel:

✔ quantifies what artists already feel

✔ reveals behavior invisible to CLIP/FID

✔ gives engineers targets to test and improve

It is the bridge. Three vocabularies with one structure.

Takeaway

This framework is not critique. It is:

diagnostic

measurable

falsifiable

actionable

It explains why AI often feels:

predictable

center-safe

breathable but constrained

And it gives tools to deliberately push past that. The kernels ultimately speak in machine, which makes images steerable (within the platforms given constraints). Through speaking to the geometry of the image, users can art direct the butterfly, moving it with ease.

Compositional reasoning vs. semantic understanding:

This work reveals a gap: models can semantically parse "extreme left third" (understand the words) but cannot geometrically execute it (place subject there), the kernel fills that gap. This suggests:

Semantic understanding ≠ Spatial reasoning

These may require different architectures:

Semantic: Transformer attention

Spatial: Geometric inductive biases

True creativity requires:

Semantic variety (what appears) ✓ Models provide this

Compositional variety (how it's arranged) ✗ Models constrain this

Stylistic variety (how it's rendered) ✓ Models provide this

Current state: 2 out of 3. Compositional control is missing dimension. To achieve human-level visual creativity, models need explicit compositional reasoning, not just semantic understanding.

This system was developed independently as a practitioner's tool. It does not build directly on institutional research or published critique systems but acknowledges adjacent dialogues in generative art, computational aesthetics, and perceptual theory

This isn't a theory. It's already running. If you're building generative tools, or trying to make them think better, this is your bridge.